Sports Illustrated Vault: Tricia Saunders

Originally Published in August 8, 1994 issue of Sports Illustrated

By Franz Lidz

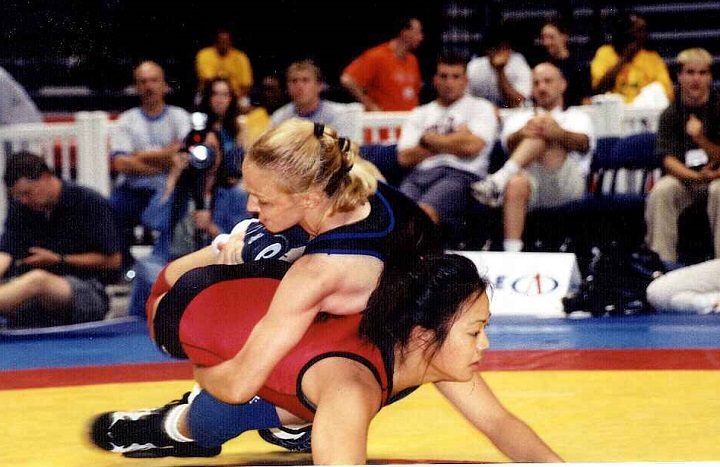

"Wrestling mats can harbor ringworm, hookworm, pinkeye, herpes, staph infections...," says this country's finest female grappler, Tricia Saunders, who earns her living as a microbiologist. "But I rarely think about it."

For the past six years the doughty Saunders, who was the first female Distinguished Member of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and is the namesake of the Hall of Fame's Tricia Saunders High School Excellence Award, has been the scourge of the fledgling women's international amateur circuit. She has never lost a match to an American, and in 1992 she became the first and only U.S. female to win a world championship, in the 110-pound weight class.

Saunders is a wiry woman of 28 with a reputation for being prickly. Astride the mats of the world, she flashes a great flush of temper. But in the living room of her Phoenix home, surrounded by her Siamese cats—Beatrice, Isis and Daphne—she looks positively beatific. Mandarin characters decorate her T-shirt, a gift from three-time world champ Xiue Zhong of China. "She beat me in the 103-pound finals at last year's worlds," Saunders says. "I like the lettering, but for all I know it means I GOT MY BUTT KICKED."

Having won five straight national titles in either the 103- or 110-pound class, Saunders knows she has only a few worthy opponents left in the world. "What's important is what goes on internationally," she said last April in Las Vegas after pinning 18-year-old Rachel Gonzales to qualify for the U.S. national team. "You won't see me getting excited about beating a first-year wrestler half my age."

Saunders has always been enormously competitive. Her grandfather, Al Steinke, was an All-America wrestler at Michigan in 1930; her father, James McNaughton, and her older brother, Jamie, were also grapplers. As a kid in Ann Arbor, Mich., she would tag along to Jamie's practices. One day Tricia, then seven, announced she was bored with watching. "Do you want to wrestle too?" asked her father.

Saunders has always been enormously competitive. Her grandfather, Al Steinke, was an All-America wrestler at Michigan in 1930; her father, James McNaughton, and her older brother, Jamie, were also grapplers. As a kid in Ann Arbor, Mich., she would tag along to Jamie's practices. One day Tricia, then seven, announced she was bored with watching. "Do you want to wrestle too?" asked her father.

"Sure," said Tricia.

"I'd roll around the carpet with my little brother, Andrew," Tricia says. "My parents never had the heart to tell me I couldn't wrestle." Neither did the Ann Arbor Wrestling Warriors Club, which made her its first girl member. Tricia's drilling partner was a squirty kid named Zeke Jones, the same Zeke Jones who went on to win a silver medal at the 1992 Olympics in the 52-kilogram class (114½ pounds) and be inducted into the Hall of Fame as a Distinguished Member in 2005.

"Zeke was always a lot lighter than me," she says. "Our matches got tougher and tougher until he finally beat me. He brags that he beat me twice, but I doubt it."

By Franz Lidz

"Wrestling mats can harbor ringworm, hookworm, pinkeye, herpes, staph infections...," says this country's finest female grappler, Tricia Saunders, who earns her living as a microbiologist. "But I rarely think about it."

For the past six years the doughty Saunders, who was the first female Distinguished Member of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and is the namesake of the Hall of Fame's Tricia Saunders High School Excellence Award, has been the scourge of the fledgling women's international amateur circuit. She has never lost a match to an American, and in 1992 she became the first and only U.S. female to win a world championship, in the 110-pound weight class.

Saunders is a wiry woman of 28 with a reputation for being prickly. Astride the mats of the world, she flashes a great flush of temper. But in the living room of her Phoenix home, surrounded by her Siamese cats—Beatrice, Isis and Daphne—she looks positively beatific. Mandarin characters decorate her T-shirt, a gift from three-time world champ Xiue Zhong of China. "She beat me in the 103-pound finals at last year's worlds," Saunders says. "I like the lettering, but for all I know it means I GOT MY BUTT KICKED."

Having won five straight national titles in either the 103- or 110-pound class, Saunders knows she has only a few worthy opponents left in the world. "What's important is what goes on internationally," she said last April in Las Vegas after pinning 18-year-old Rachel Gonzales to qualify for the U.S. national team. "You won't see me getting excited about beating a first-year wrestler half my age."

Saunders has always been enormously competitive. Her grandfather, Al Steinke, was an All-America wrestler at Michigan in 1930; her father, James McNaughton, and her older brother, Jamie, were also grapplers. As a kid in Ann Arbor, Mich., she would tag along to Jamie's practices. One day Tricia, then seven, announced she was bored with watching. "Do you want to wrestle too?" asked her father.

Saunders has always been enormously competitive. Her grandfather, Al Steinke, was an All-America wrestler at Michigan in 1930; her father, James McNaughton, and her older brother, Jamie, were also grapplers. As a kid in Ann Arbor, Mich., she would tag along to Jamie's practices. One day Tricia, then seven, announced she was bored with watching. "Do you want to wrestle too?" asked her father."Sure," said Tricia.

"I'd roll around the carpet with my little brother, Andrew," Tricia says. "My parents never had the heart to tell me I couldn't wrestle." Neither did the Ann Arbor Wrestling Warriors Club, which made her its first girl member. Tricia's drilling partner was a squirty kid named Zeke Jones, the same Zeke Jones who went on to win a silver medal at the 1992 Olympics in the 52-kilogram class (114½ pounds) and be inducted into the Hall of Fame as a Distinguished Member in 2005.

"Zeke was always a lot lighter than me," she says. "Our matches got tougher and tougher until he finally beat me. He brags that he beat me twice, but I doubt it."