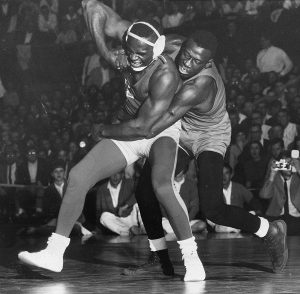

Sports Illustrated Vault: Bobby Douglas

Originally Published in March 9, 1992 issue of Sports Illustrated

By Kenny Moore

Four feet in front of Bobby Douglas's desk in his third-floor office at Arizona State is the sky. A wall of windows reveals the campus below, a rectilinear oasis of palms, citrus and tawny masonry rising out of a land of pale rose rock. Between the desk and the windows is wedged a single chair. To speak with the 1992 U.S. Olympic wrestling coach, you settle into this seat and wait, because the man is so consumed by college competition, Olympic planning, recruiting, writing and club coaching that he lives a perpetual, unclosable 10 minutes behind schedule.

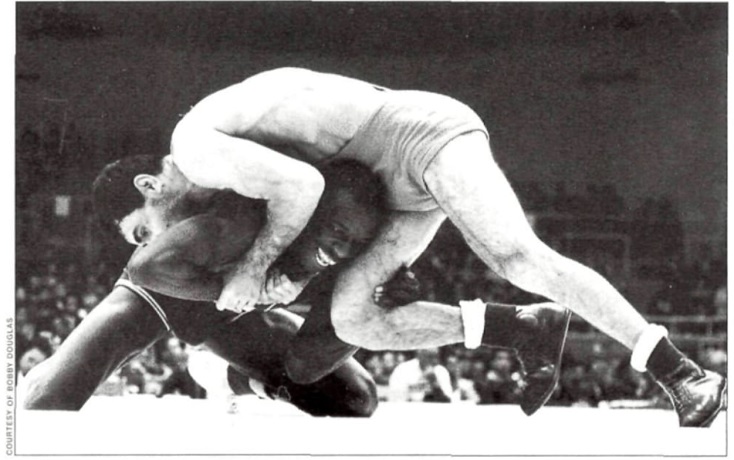

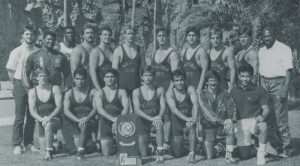

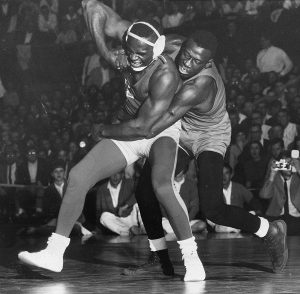

You study silver runner-up trophies from the 1989 and 1990 NCAA championships and photos of Douglas and his team rejoicing in the Sun Devils' 1988 victory, the first NCAA wrestling title ever won under an African-American coach.

You study silver runner-up trophies from the 1989 and 1990 NCAA championships and photos of Douglas and his team rejoicing in the Sun Devils' 1988 victory, the first NCAA wrestling title ever won under an African-American coach.

The heel of your hand finds bare metal. The vinyl on the chair's arms is split, and the foam padding has frayed to the rivets.

This is where each Arizona State wrestler sits alone before his coach. This is where strong men writhe.

You have been warned that Douglas, a Distinguished Member inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in 1987, can be intimidating, tending, in the way of many wrestlers, to feel people out, to give nothing away. Indeed, when he appears, in a sweatsuit, Douglas keeps his sunglasses on. He is 5'7" and compact. At 49, the wisps of gray in his short hair seem like fuses leading to the body of a cast-iron cannon. But when you are finally able to tell him that you want his sense of what is important in his story, the shades come up, and he takes your hand, powerfully, and draws you within the pale.

"We are always, each of us, on the end of a long story," he says, "and wrestling's is as ancient as humanity's. I was saved and formed by two men, my grandfather and my high school coach, and they did it with the culture of wrestling. So, as a teacher, hell, I ache to tell my story."

It comes out awkwardly at first, because of its unexpected sweep. Clumps of Ohio childhood are mixed with prehistory. Horrific loss is juxtaposed against sporting triumph. A personal quest is intermingled with blood rituals and post-cold war diplomacy. But as Douglas spreads photographs on the desk and unfolds old correspondence and pulls down books, his story takes on the clarity of desert night air.

It comes out awkwardly at first, because of its unexpected sweep. Clumps of Ohio childhood are mixed with prehistory. Horrific loss is juxtaposed against sporting triumph. A personal quest is intermingled with blood rituals and post-cold war diplomacy. But as Douglas spreads photographs on the desk and unfolds old correspondence and pulls down books, his story takes on the clarity of desert night air.

Douglas was born in Bellaire, Ohio, in 1942, to Belove Davis and Eddie (Blue) Douglas, an itinerant boxer and mine-worker who was in prison for theft at the time. Belove had been an invalid since an automobile accident crushed her pelvis when she was 27. "She had so much pain in her life, she was alcoholic," says Douglas. "We lived in a third-floor apartment in the ghetto. It was a welfare environment. People survived as they could, and one way was with the numbers racket. I remember when I was maybe three being sent apartment to apartment delivering slips of paper with writing on them."

Douglas's fundamental childhood memory still sometimes tears him from sleep. "I was three or four. I was with my mother in bed on a hot evening," he says, his tone controlled. "There was banging on the door, not a knock. It scared my mother. Then the door came down. A guy came in, and they were fighting. He pinned her against the wall. There was blood. I couldn't tell where it was from. She was screaming for me to leave. I was thrown off the bed and hit my head on something, but I crawled out through the blood and got downstairs, and the people there called the police. I can't remember anything more until I was five."

Click to Read Full Story

By Kenny Moore

Four feet in front of Bobby Douglas's desk in his third-floor office at Arizona State is the sky. A wall of windows reveals the campus below, a rectilinear oasis of palms, citrus and tawny masonry rising out of a land of pale rose rock. Between the desk and the windows is wedged a single chair. To speak with the 1992 U.S. Olympic wrestling coach, you settle into this seat and wait, because the man is so consumed by college competition, Olympic planning, recruiting, writing and club coaching that he lives a perpetual, unclosable 10 minutes behind schedule.

You study silver runner-up trophies from the 1989 and 1990 NCAA championships and photos of Douglas and his team rejoicing in the Sun Devils' 1988 victory, the first NCAA wrestling title ever won under an African-American coach.

You study silver runner-up trophies from the 1989 and 1990 NCAA championships and photos of Douglas and his team rejoicing in the Sun Devils' 1988 victory, the first NCAA wrestling title ever won under an African-American coach.The heel of your hand finds bare metal. The vinyl on the chair's arms is split, and the foam padding has frayed to the rivets.

This is where each Arizona State wrestler sits alone before his coach. This is where strong men writhe.

You have been warned that Douglas, a Distinguished Member inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame in 1987, can be intimidating, tending, in the way of many wrestlers, to feel people out, to give nothing away. Indeed, when he appears, in a sweatsuit, Douglas keeps his sunglasses on. He is 5'7" and compact. At 49, the wisps of gray in his short hair seem like fuses leading to the body of a cast-iron cannon. But when you are finally able to tell him that you want his sense of what is important in his story, the shades come up, and he takes your hand, powerfully, and draws you within the pale.

"We are always, each of us, on the end of a long story," he says, "and wrestling's is as ancient as humanity's. I was saved and formed by two men, my grandfather and my high school coach, and they did it with the culture of wrestling. So, as a teacher, hell, I ache to tell my story."

It comes out awkwardly at first, because of its unexpected sweep. Clumps of Ohio childhood are mixed with prehistory. Horrific loss is juxtaposed against sporting triumph. A personal quest is intermingled with blood rituals and post-cold war diplomacy. But as Douglas spreads photographs on the desk and unfolds old correspondence and pulls down books, his story takes on the clarity of desert night air.

It comes out awkwardly at first, because of its unexpected sweep. Clumps of Ohio childhood are mixed with prehistory. Horrific loss is juxtaposed against sporting triumph. A personal quest is intermingled with blood rituals and post-cold war diplomacy. But as Douglas spreads photographs on the desk and unfolds old correspondence and pulls down books, his story takes on the clarity of desert night air.Douglas was born in Bellaire, Ohio, in 1942, to Belove Davis and Eddie (Blue) Douglas, an itinerant boxer and mine-worker who was in prison for theft at the time. Belove had been an invalid since an automobile accident crushed her pelvis when she was 27. "She had so much pain in her life, she was alcoholic," says Douglas. "We lived in a third-floor apartment in the ghetto. It was a welfare environment. People survived as they could, and one way was with the numbers racket. I remember when I was maybe three being sent apartment to apartment delivering slips of paper with writing on them."

Douglas's fundamental childhood memory still sometimes tears him from sleep. "I was three or four. I was with my mother in bed on a hot evening," he says, his tone controlled. "There was banging on the door, not a knock. It scared my mother. Then the door came down. A guy came in, and they were fighting. He pinned her against the wall. There was blood. I couldn't tell where it was from. She was screaming for me to leave. I was thrown off the bed and hit my head on something, but I crawled out through the blood and got downstairs, and the people there called the police. I can't remember anything more until I was five."

Click to Read Full Story